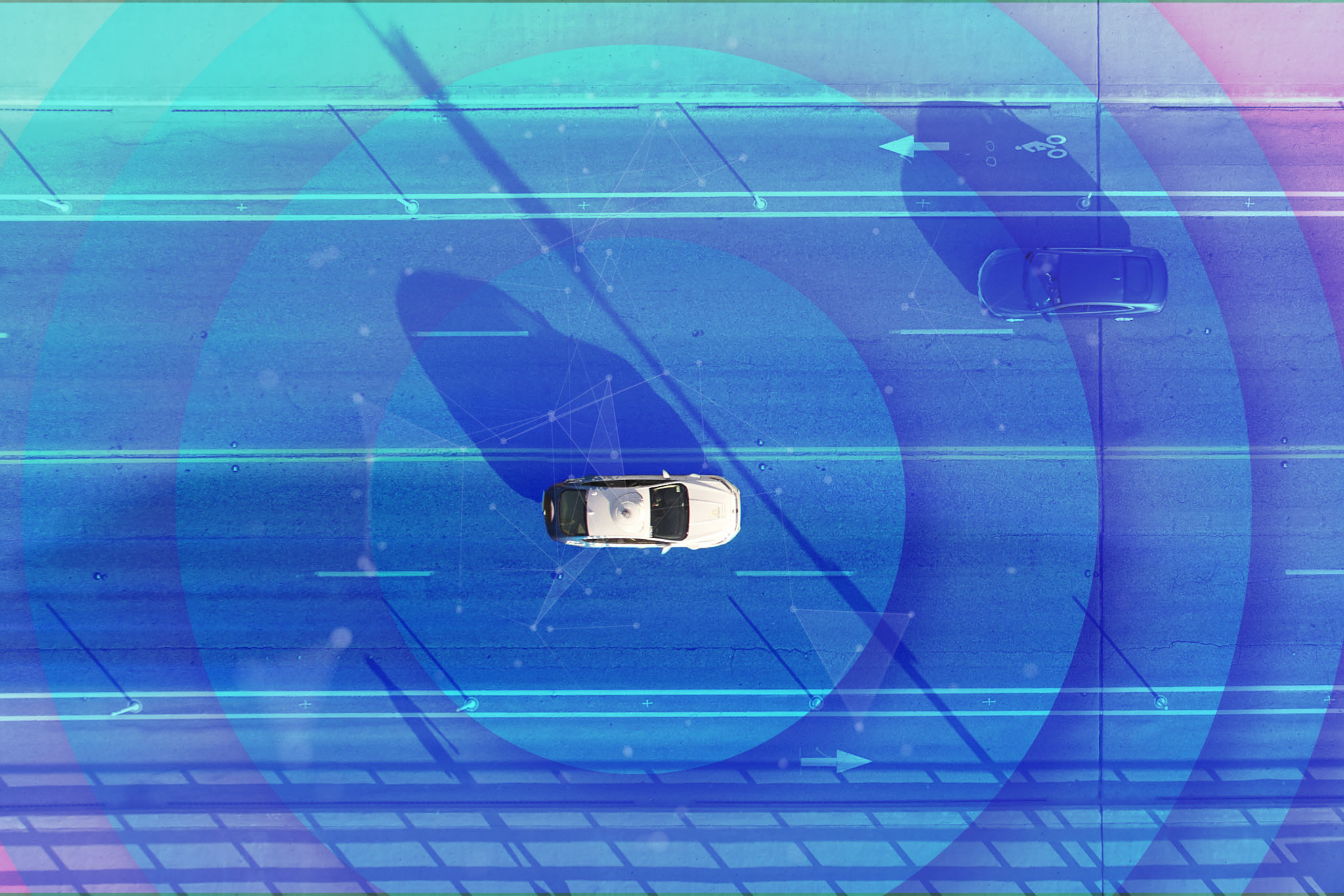

People often ask me who is winning the self-driving car race: Is it Tesla? GM? Google? Nvidia? You guys at Argo? Some of the folks asking are investors. Some are looking for a job. All of them are trying to evaluate the state of the self-driving sector.

But all of them are using the wrong framing device.

If you want to predict a winner, you’ve got to know what kind of race is being run, or if it’s even a race at all. The first person to build a new kind of plane isn’t necessarily going to build a successful airline. They may not even survive in the plane-building business.

So why do people keep trying to call things races that aren’t really races? I get that simplifying complex things makes them easier to talk about, and it can generate traffic. But if something isn’t a race, then calling it a race makes it harder to understand, and that can have all sorts of negative consequences.

For example, Nokia thought they had won the cellphone race in late 2007. A lot of people did, and they all missed that Nokia wasn’t in a cellphone race, but actually in the bigger, longer, portable devices game. The cellphone era was ending, the smartphone was about to begin, and Apple’s iPhone had launched a few months before the now hilarious Forbes cover that said:

NOKIA

One Billion Customers

Can Anyone Catch The Cellphone King?

Today Nokia is a shell of its former self, and Apple just passed a $3 trillion valuation.

There is no race for self-driving because “self-driving” — like elevators, flight, shipping, railroads, and cars — isn’t a monolithic thing with an endpoint. Self-driving is a constellation of technologies, around which all kinds of businesses have already been built, more are being built right now, and new ones will be built in the future.

Understanding the future of the self-driving game is a lot easier once you see all the ways it differs from a race.

Races are linear. The real world isn’t.

Notice something? No matter how long a race is, no matter how many twists and turns, a race has only one path to victory. But technological development doesn’t work that way, and business certainly doesn’t. If life was that easy, experimentation wouldn’t be necessary, projects would never stall, and businesses would never pivot. Everything looks obvious in hindsight, but in his 1935 essay Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact, science historian Ludwik Fleck wrote of why the “straight path to knowledge” is a fiction. True progress happens in fits and starts, and the most successful people in the world will tell you there is no success without failure.

Meeting arbitrary milestones doesn’t necessarily mean a company is about to win, nor does a hiccup mean they are about to lose. Don’t get me wrong, these can be important and exciting, and I devour the latest news like anyone else, but what really matters is the long game, and whether a company is progressing toward becoming a profitable business that can stand the test of time.

A race has a clear start and finish line

When did any of our transportation “races” begin or end? What did those start and finish lines look like? No one can say, because history isn’t that simple.

Does being first matter? People are still arguing over who built the first plane. If you think it was the Wright Flyer, some Greek, French, Italian and German historians want to have a word with you. Can anyone name the first American airline literally out of the gate? Was it the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line in 1914? Or maybe it was Western Air Express in 1926? They’re gone, like hundreds of other aviation and airline startups.

Size doesn’t guarantee survival either. TWA used to be one of “The Big Four” U.S. domestic airlines, and Pan Am was once the largest international airline based in the United States, and unofficial U.S. flag carrier. What’s left of TWA? A groovy 60’s themed hotel in their old JFK terminal, designed by Eero Saarinen.

As for Pan Am, now they’re just a board game you can buy for $25.

Elevators had some really early first movers too. Pharaoh Khufu put an elevator in a pyramid 4500 years ago, and in 214 BC Archimedes’ giant claw allegedly destroyed the Roman fleet at Syracuse. I’ve never ridden in a Khufu or Archie branded elevator, so they obviously didn’t “win” either.

But Alex, they weren’t in the elevator business. Once Elisha Otis invented the first safety elevator in 1854, it was game over.

Uh, not quite.

Otis’ legendary 1854 demonstration (pictured above) wasn’t the finish line for elevator safety, nor was it the start line for Otis’ rise to dominance. Safety had been evolving in Europe and the United States for decades, and continued to improve after Elisa Otis’ death in 1861. It wasn’t until his two sons began rolling up the US elevator market in 1898 that the company we know today began to take shape. But even that wasn’t the finish line for elevators, because Otis’ sons weren’t the only ones scaling an elevator business at the dawn of the 20th century.

Racing is winner-take-all. The real world isn’t.

Winner-take-all narratives are easy to believe and fun to tell, but they’re pretty hard to find in the real world. Despite the apparent ubiquity of the world’s popular elevator, today Otis only commands 12% of the global elevator market. Schindler, the Swiss company that made the elevator in my Miami condo building, has 11%. One hundred and thirty-five years into the modern elevator business, 5 companies control approximately 50% of the market.

So where are the winner-take-all verticals in transportation? There aren’t any, because it’s winners-take-most. From elevators to flight, shipping, railroads, cars, bicycles, and even unicycles — pretty much anything that involves moving people or goods around — multiple winners rose above the forest of history. And new ones continue to rise alongside them, because human nature blows the notion of one-time races out of the water.

Victory is always fleeting, because it draws competition like a magnet.

In real Life, competition never ends

When Lewis Hamilton or Max Verstappen win an F1 race, the sport doesn’t magically come to an end. If racing worked that way, the first F1 race in 1950 would also have been the last. We are a competitive species, not just physically, but intellectually and emotionally. Imagine a world where companies were held to the rules of a single car race: the first one to release a product wins, and everyone is satisfied. Innovation and competition end. Game over.

But that’s ridiculous. It was ridiculous in 1889, when U.S. Patent Office Commissioner Charles H. Duell allegedly said his office would eventually close, because “everything that can be invented has been invented.”

If self-driving isn’t a race, what game is it?

Every game has victory conditions, and from elevators to flight, shipping, railroads, and cars, history is clear: the end state is a winners-take-most equilibrium. It’s also true for smartphones. Fifteen years after Forbes declared Nokia the cellphone king, no one company has taken its place. Despite the iPhone’s dominance in the media and pop culture, Samsung outsells Apple by single digits almost every quarter, and approximately 50% of the global market is dominated by five companies, three of which many Americans haven’t even heard of: Xiaomi, Vivo, and OPPO.

Check out the global smartphone market 2018-2021 for yourself.

If the end state of global multiplayer markets is a winners-take-most equilibrium, then victory conditions must include the creation of a profitable business, global scale, and the ability to maintain market share among the winners.

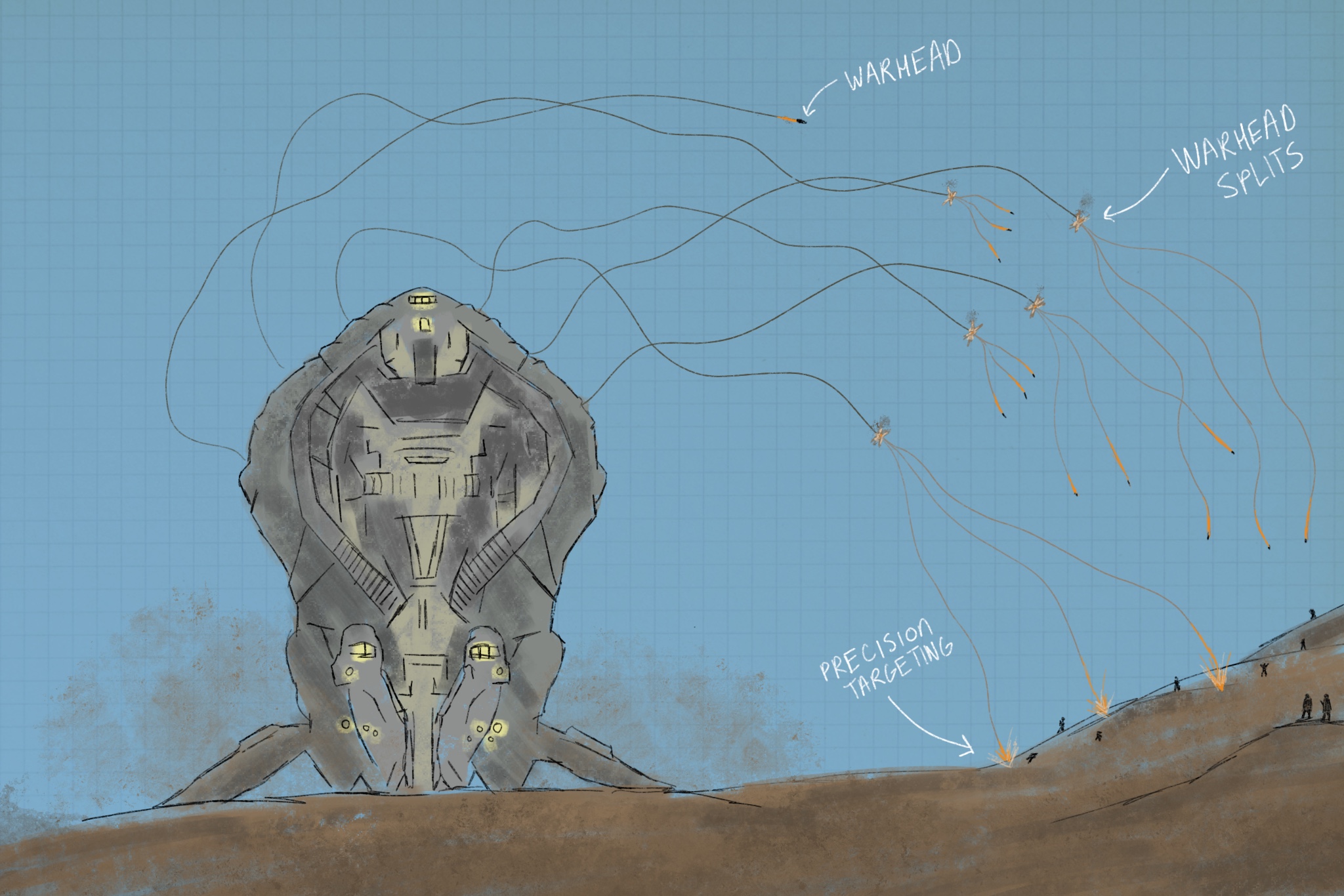

If that sounds like a long and complicated game, it is. But there is a famous board game of grand strategy that closely resembles the self-driving industry at its highest level. It’s a game played on a map of the world, and it has three distinct phases: setup, combat, and equilibrium, also known as when the last couple of players are too big to beat…and everyone calls it a night.

The self-driving industry is in the setup phase of that game right now, with players assessing the map, creating alliances, and putting pieces on the board.

Can you guess the game? If you were born before 1985, there’s a good chance you’ve got this in the basement or in the closet, and there’s an even better chance you’re going to understand the future of self-driving before I reveal all next week.